It may be difficult, but it is possible to create a corporate taxation system that better reflects the changes in the global economy. The current international corporate tax architecture is fundamentally out of date. The European Commission estimates that GAFA (Google – Amazon – Facebook – Apple) such firms pay a tax rate on their profits of 9 percent on average, compared to 23 percent for traditional companies.

Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), provided opening remarks at the release of a new major study on international taxation by the IMF on March 25, 2019, at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). Michael Keen, deputy director of the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department, presented the findings from their latest policy paper, “Corporate Taxation in the Global Economy.” Watch the video with a great panel discussion with Vitor Gaspar from the IMF, Mindy Herzfeld from the University of Florida Levin College of Law, and Gary Clyde Hufbauer from the Institute.

Christine Lagarde mentioned the quote:

The hardest thing in the world to understand is the income tax. Albert Einstein

IMF staff regularly produces papers proposing new IMF policies, exploring options for reform, or reviewing existing IMF policies and operations. The policy paper Corporate Taxation in The Global Economy, explores options that have been suggested for their future development, including several now being considered in global fora and considering the contribution of the Fund to debates and processes now underway.

The IMF is not a standard setting body in this area. Intensive discussions of possible changes to the international tax system are now underway in the Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) / the OECD, and the paper is intended to complement that work, reflecting the distinct contribution that the IMF’s broad membership, mandate, expertise and capacity building work position it to make.

The paper does not endorse any specific proposals for international tax reform. It recognizes that views differ widely. Rather the paper identifies and discusses potential criteria by which alternatives might be assessed – with special attention to the circumstances of developing countries—and provides some empirical analysis to support discussions.

The paper stresses the need to maintain and build on the progress in international cooperation on tax matters that has been achieved in recent years, and in some respects now appears under stress. It considers the supportive role that the Fund can play in this context, including by drawing on its capacity building work to inform the standard setting that others lead, and stresses the importance of cooperation among the international organizations active in this area, including through the Platform for Collaboration on Tax.

IMF – Executive Board Assessment

As an important element of the current debate, Directors welcomed the discussion on tax challenges associated with digitalization. They recognized that this is a difficult issue, technically and politically, and that views on whether special treatment is needed, and if so in what form, continue to differ widely. For the long term, a number of Directors considered that it would not be desirable or feasible to design ring-fenced solutions. Directors looked forward to the final report from the OECD to the G-20 in 2020, which could serve as a basis for a cooperative approach going forward.

Directors underscored the need for an inclusive process for discussing international taxation, especially as fundamental issues in the allocation of taxing rights come under discussion. Many Directors felt that the current governance arrangements, with the OECD as a central body and standard-setter and supported by the Inclusive Framework, are broadly appropriate. At the same time, many Directors saw room for improvements, including to enhance the representation of developing and low-income countries in the decision-making process.

Directors emphasized the important role of the Fund in the area of international corporate taxation, focusing on its universal membership, macroeconomic perspective, and analytical expertise. They stressed in particular the value of Fund advice and extensive capacity building, helping member countries to implement best practices on tax policy and administration. A number of Directors stressed that efforts to bridge data gaps would need to take account of confidentiality issues and limited capacity in many developing countries. They noted that the Platform for Collaboration on Tax provides a useful framework for bringing together the IMF, OECD, UN, and World Bank, and could continue to play an active role in supporting international tax coordination.

First, the ease with which multinationals seem able to avoid tax, and the three-decade long decline in corporate tax rates, undermines faith in the fairness of the overall tax system. Second, the current situation is especially harmful to low-income countries, depriving them of much- needed revenue to help them achieve higher economic growth, reduce poverty, and meet the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. Advanced economies have long shaped international corporate tax rules, without considering how they would affect low-income countries.

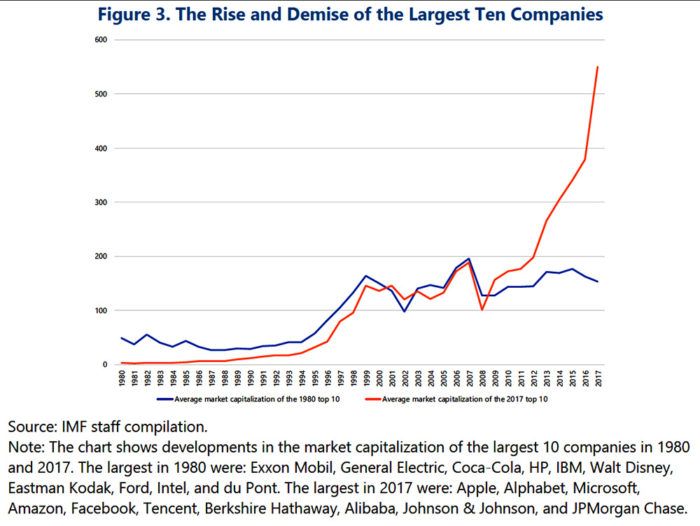

Issues raised by digitalization have become a centerpiece of discussions on the future of international corporate taxation. The context is the increasing use of digital technologies throughout business and the rise of new business models, exemplified by a few well-known firms heavily dependent on digital technologies – many of them provide a service without charge (though more accurately regarded as a form of barter: access to the service in return for personal information provided in the act of using it). Many of these firms are highly profitable yet have in many cases paid relatively little tax anywhere.

The international corporate tax system is under unprecedented stress. The G-20/OECD project on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) has made significant progress in international tax cooperation, addressing some major weak points in the century-old architecture. But vulnerabilities remain. Limitations of the arm’s-length principle—under which transactions between related parties are to be priced as if they were between independent entities—and reliance on notions of physical presence of the taxpayer to establish a legal basis to impose income tax have allowed apparently profitable firms to pay little tax. Tax competition remains largely unaddressed. And concerns with the allocation of taxing rights across countries continue.

Alternative international tax architectures differ not only in their economic properties, but in how far they depart from current norms and the degree of cooperation they require.

The economic impact and administrability of these schemes requires further analysis—especially for emerging and developing countries.

Some improvements can be achieved unilaterally or regionally, but more fundamental solutions require stronger institutions for global cooperation.

GAFA: Google – Amazon – Facebook – Apple

How to deal with tech giants?

THE DIGITALIZATION DEBATE

Dealing with the corporate tax implications of digitalization and new business models is highly contentious, politically and intellectually. If there was any consensus in the initial G-20/OECD report on digitalization,27 as in an earlier report by the European Commission (2014), it was that attempts to isolate for special treatment a ‘digital economy’ (or ‘digital activities’) are misplaced, given how pervasive these technologies are, and so unpredictable is their future development. The implication was that measures seeking to ‘ring-fence’ a subset of firms or activities would be inappropriate. However, policy in many countries has moved rapidly in the direction of short-term measures while the search for a common approach continues at the OECD, a final report to the G-20 being due in 2020.

Varieties of Digital Services Tax

The EU and U.K. proposals have similar scope – focused on social media, search engines and intermediation services – but take different approaches to measuring user value. The EU takes a volume-based approach, allocating revenue in proportion to how often an advert has appeared on users’ devices and the number of users having concluded transactions on a particular platform, with the location of the user determined based on their internet protocol (IP address). The U.K. in contrast envisages a value-based approach, looking for example to the value of the advertising sales targeted at U.K. users, and the commissions generated by facilitating a transaction with U.K. users. Questions remain as to how the definition of the user would determine the apportionment of revenue from cross-border transactions, and how to apportion revenue derived from the sale of multinational data sets.

Other countries (including India, Chile and Uruguay) have opted for withholding or ‘equalization’ taxes on payments for advertising and other specified digital services made by residents to non-resident companies, avoiding the need to apportion revenue attributable to domestic users. Simpler to design and administer, such taxes risk avoidance by having related offshore entities purchase the services.

Some low-income countries (Benin, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia) have recently introduced taxes on the use of certain digital services, though these are taxes not on the revenues of service providers but on access to digital services, such as social media.

– Do you agree that the international corporate income tax system requires substantial reform?

– Do you believe that ‘digitalization’ requires specific tax solutions, or rather that it is impossible/undesirable to ring-fence “digital” activities or firms?

– Do you agree that IMF advice should reflect the potentially differing impacts on lowincome countries of possible approaches to reforming the tax architecture?

The current international corporate tax architecture is fundamentally out of date. By rethinking the existing system and addressing the root causes of its weakness, all countries can benefit, including low-income nations.

Christine Lagarde

PIIE – Peterson Institute for International Economics

The Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) is a private, nonpartisan nonprofit institution for rigorous, intellectually open, and indepth study and discussion of international economic policy.

The Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) is a private, nonpartisan nonprofit institution for rigorous, intellectually open, and indepth study and discussion of international economic policy.

Since 1981 PIIE has provided timely and objective analysis of, and concrete solutions to, a wide range of international economic problems. It is one of the few economics think tanks that are widely regarded as “nonpartisan” by the press and “neutral” by the US Congress.

Join the Global Corporate Taxation & Digitalization Debate

The Global Economy needs a lively intellectual debate and pragmatic solutions!